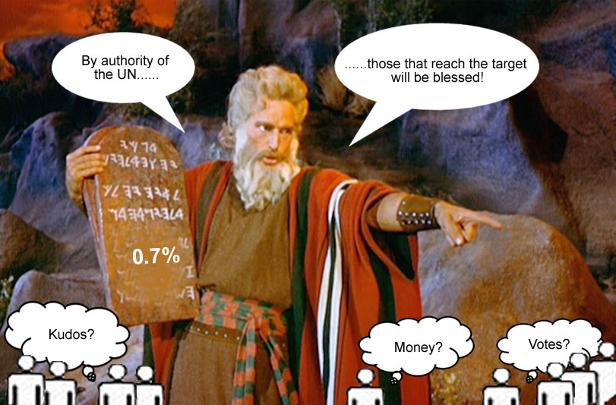

Reasons for the 0.7% myth

Nothing quite illustrates the lost state of the aid industry as the UK Government’s headless, self-satisfied and largely unchallenged rush to reach the UN’s 0.7% spending target. Although the sixth country to join the 0.7% club, the UK is by far the biggest to do so and now is the second largest bilateral donor. But what is seen by most in the aid industry as a cause of celebration, in practice illustrates its inability to honestly consider its efficacy, motives and role.

The 0.7% target emerged in 1970 as a UN Resolution after a decade of assorted commissions and studies. Today, four sets of reasons are cited to justify its relevance.

Technical/developmental: the target’s original rationale was that this was the finance gap that should be filled for countries to achieve acceptable levels of growth. However, in an era of more private sector investment and remittances and as the importance of more qualitative factors such as institutional capacity is recognised, the basic technical rationale of five decades ago is now widely dismissed. Few seriously believe that there is any legitimate technical reason pointing to 0.7% as the “right” amount of aid.

Moral: given that 0.7% is an arbitrary figure emerging from political haggling, and that believers in the omnipotence of the UN are now thin on the ground, the moral arguments stem from the general impulse that ‘more is better’. And that those who give most are also ‘better’. This essentially is a charity/whip-round/rattle-the-collecting-cans/welfare state view of international development. Not ‘evidence-based’ but responding to unalloyed instinct. And it fails to take account of a reality known to any experienced project manager that, counter-intuitively perhaps, more aid often makes things worse. As the ex-DFID Chief Economist, Adrian Wood noted recently: “If you give a country too much aid for too long you damage its basic governance structure because the politicians pay more attention to the donors than they do to their citizens”.

Commercial/pecuniary: the UK’s aid industry has ballooned in recent years. The largest commercial contractors have trebled their income (and profits) in the course of this Parliament. ODI, the UK’s largest research organisation, has doubled. Most NGOs are larger and more reliant on DFID – ironic given their non-government status – than ever before (Oxfam, for example, one of the more independent NGOs, is still around 40% DFID-dependent). To this must be added the burgeoning ‘service provider’ sector, especially the army of value-for-money, research and evaluation specialists required to make sense of/dress up the spending splurge in dispassionate tones of measured progress. And the (paid) communication and exchange platforms required to shovel information around. Together it all contributes to a disparate band united by a singular realisation; they know on which side their bread is buttered; they all need DFID’s bloated budget.

Political: increasing the aid budget has been one of the pillars of the UK Government’s – and the Conservative Party’s – rebranding efforts. No longer the “nasty party”, but ‘international’, ‘outward-looking’ and ‘concerned’ – all also qualities that appeal to their liberal coalition partners. The 0.7% aid target fits a political purpose now. Whether this still applies after May’s general election – when the country’s political landscape may have moved further Right – is more doubtful.

The 0.7% target is a convenient cause that serves the alignment of pecuniary and political vested interests shaping the UK’s aid industry. Without valid technical or moral basis, it is a dangerous myth that distorts development endeavours, focusing attention on quantity and inputs and not on quality and genuine achievement. Adorned in the self-righteous language of international solidarity and concern, it is a lazy rallying cry for a self-serving, sprawling bandwagon. Far from being an indicator of aid's responsiveness to the poor, it is primarily about aid as a vanity project for the rich.

And where are development agencies on these issues? It is to the enduring shame of the development sector as a whole that no mainstream organisation has publicly questioned the worth of the 0.7% policy. On the contrary, the various umbrella lobby groups, such as the Turn Up Save Lives campaign, spout consciously-misleading ‘facts’ on aid money’s ‘deliverables’ – children in school, children ‘saved’ – that say nothing about whether aid is addressing the underlying causes of poverty. Or about the more obvious beneficiaries of aid spending – themselves.

Poverty reduction and tax avoidance: PwC’s new ‘complementary’ strategy?

As its budget has grown evermore stratospheric, so has the closeness of DFID’s relationship with large private contractors, irrespective of whether they may represent odd bedfellows for an agency whose mission statement is to “tackle the underlying causes of poverty”. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) in the UK, with revenues of £2.8bn and more than 14,000 staff, is one of the ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms and increasingly one of DFID’s most trusted partners. In the words of Managing Director, Kevin Ellis, “The work of DFID is completely complementary to PwC. Together we can make a big difference”.

So what does “complementary” and “difference” mean in relation to one of PwC’s main activities, tax advice? PwC is the largest tax business in the UK. In February the head of the House of Commons Public Affairs Committee, referring to its large activities in Luxembourg, accused PwC of “promoting tax avoidance on an industrial scale”. This also comes at a time when wealth inequalities – with the world’s 85 richest individuals owning more than the 3.5bn poorest – are rising, a trend hastened by the burgeoning tax avoidance industry. Thanks to it, the global super-rich and the biggest corporations often escape their tax paying responsibilities. Undoubtedly, this is an area where PwC is making a “big difference”. But how this massive private gain can be seen as compatible with the public cause of tackling poverty’s “underlying causes” is a mystery.

While not in the same league as its tax avoiding core competence, PwC has also been alive to the growing profit possibilities offered by the new DFID, and its 70% budget growth in 5 years. PwC has been especially adept at winning fund management roles, such as the £350m Girls Education Challenge Fund, which tend be non-technical in nature, channelling money and taking a margin in the process. The Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) is another large (£50m) DFID project,

in this case also offering a chance to build relations with, and cross-sell to, potential new clients – assisted by the uncanny similarity between the CDKN and PwC logos.

At the other end of the budget spectrum, PwC now manages the BEAM exchange, “a one-stop shop for sharing knowledge and learning about market systems approaches for reducing poverty”. Presumably, in keeping with the general PwC ethos, this means systems in which participants scarcely pay tax, though skills in tax avoidance, even without the undoubted expertise of PwC, are already rather advanced in most developing countries (the average value of taxes in low-income African countries is 17% of GDP compared with 40% in the EU). While BEAM only amounts to £4m, its real value is the opportunity it presents to enhance the PwC brand within DFID’s fastest growing budget area, economic development. As part of this process of DFID relationship-building, PwC also provide staff on a pro-bono basis on “how business can join the development push”, something in which it is, self-evidently, well-qualified.

In most of its DFID projects, PwC are also leading consortia of development organisations. The CKDN grouping, for example, includes the research organisation the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), and Lead International from the not-for-profit sustainability area as well as, in the capacity of Executive Chair, Simon Maxwell, ex-ODI Head, adviser to DFID and bigwig of the development world. The overall effect is to mainstream PwC within development processes and discussion, and in doing so reduce the chances of unwanted scrutiny of its role. Worries over PwC’s compatibility with development aims have been swept aside. Certainly it has seeped into the core of DFID, an organisation whose head, Secretary of State, Justine Greening, happens to be an accountant by profession. In fact, one trained by PwC.

Letters: DevBalls Readers Speak....

Sir, If the law is changed to require UK governments to devote 0.7% of national income to aid, DFID clearly is not going to be able to spend it wisely or well. There is an obvious and bold solution to this problem. Reclassify half the aid budget as ‘New Developmental Conflicts’ (Neo-Dev-Cons) and allocate it to the Ministry of Defence. This would provide the means for a more pro-active approach to exerting targeted and aggressive transformational influence on under-performing nations, belligerents, laggards, bad beardies and moustachioed ne’er-do-wells.

In doing so we would also create the demand for DFID’s main relief and reconstruction service offerings and so develop new channels to spend its still fiendishly large and difficult-to-spend budget and strengthen the UK’s brand in the conflict market. I have one or two ideas on immediate targets – and a track record of delivery. My company would be pleased to assist in delivering such a policy.

It’s time to step up our War on Poverty!

Tony Blair - Global consultant on Peace, Faith, Healing and Commerce (and the odd War)

_____________________________________

Sir, I must protest at your continuing negative depiction of UK aid contractors. This is just another example of doing Britain down and bad-mouthing British success.

That the Poverty Business is booming is a cause for congratulations! We should be celebrating the growth in overall volumes which, together with robust maintenance of healthy margins, has kept profitability and earnings competitive. This has allowed our industry to offer the kind of packages necessary to attract and incentivise talent that would otherwise be drawn to competing sectors such as investment banking, property speculation and leach cultivation.

We contractors are fed up having to apologise for success. With the new commitment to spending (0.7%), Britain is leading the way in the Global Poverty Business. We look forward to more years of exciting growth and cooperation with DFID. These are good times to be in Poverty – we should be proud!

Walter V Wisewank - DFID Key Suppliers Group

_____________________________________

Sir, We reject entirely the foul suggestion in DevBalls’ current edition that there is a contradiction between PwC’s international development and tax avoidance activities. We would point out:

The great impact of PwC’s work on the (admittedly often unreported and well-hidden) poor of Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands.

That, faced with niggardly, killjoy tax regimes, even the richest can end up on the slippery slope that leads from billionaire to millionaire to ….. well, eventually, the snapping jaws of poverty. We see tax avoidance really as an enlightened and early, poverty-prevention initiative.

PwC and DFID (“Hand-in-hand, we can make a difference!”)

_____________________________________

Dear Editor,

Thank God for DevBalls! I have been in development for thirty-seven-and-a-half years and can safely say that you are spot on. Never has the aid industry been as grotesque as now.

However, can I ask you to stop? It all may well be true, but there’s a serious issue here; we’re talking about livelihoods after all (mine in particular).

And I worry that the Daily Mail will get hold of this (maybe you are the Daily Mail?)

Name and address withheld.

_____________________________________

Hi, You’re absolutely right about those bastard contractors. They earn far too much and give far too little work and pay miserable rates to development researchers such as myself. All they think about is money.

But keep on socking it to the man! I could tell you some stories, let me tell you! (I won’t of course – far too close to home, you know how it is).

Dave the Rave – on behalf of all the small guys out there!

_____________________________________

The thriving Blair legacy

News that Tony Blair has been the recipient of a Global Legacy Award from Save the Children (STF) prompts the question of what his legacy really is for international development? It’s likely that sour ingrates in places such as Iraq and Syria – indeed possibly throughout the world – may have a view on this. And, while the final transmogrification of DFID has happened under the current government, this is essentially a continuation of the course set under Blair – the spending, the chequebook-is-the answer mentality, the dominance of political gesture over development substance.

But a new Blair legacy is emerging. With that special arrogance only felt by the rich and politically powerful, some of the Blair era’s main characters are beginning to traverse the globe - do-gooding, dispensing their self-appointed wisdom and, for some at least, making a tidy sum in the process.

TB himself, of course, leads the way with his unique mix – the Blair Blend – of ‘good deeds’ for the world’s unfortunates (eg Rwanda), lucrative advice to dodgy governments (eg Kazakhstan), Saudi oil companies and investment bankers (eg JP Morgan), and obscure ‘peace envoy’ roles in the Middle East. TB does dictators and the poor. TB does investment banking and peace. TB does fees and pro-bono. TB does not-for-profit and (especially) profit. TB does …. it all! All of which may not have generated huge benefits for the planet’s people but have proved a tidy earner for TB. Estimates of his wealth extend up to £100m, although he says it’s closer to a paltry £10m. And now, hot on the heels of his Philanthropist of the Year award from GQ magazine comes the Global Legacy Award from STF, doubtless helped by the fact that its UK CEO (Justin Forsyth) previously worked for TB and his former Chief of Staff, Jonathan Powell, is on the Board of STF.

No one could accuse Gordon Brown, Chancellor and then successor to TB as Prime Minister, of lining his pockets from his engagements in the development sphere. But what particular expertise does he bring? Well, as a UN Global Envoy for Education, this might be expected to be a key competence. Under his financial stewardship, DFID made education a major priority, piling large amounts into the state education systems of countries such as Ghana and Uganda, especially in teacher training, books and schools. Which all sounds good and wholesome. Except it failed. A report from the National Audit Office in 2010 found that while enrolment had increased, attainment rates hadn’t. In other words, more children were turning up but to learn nothing with, for example, “little or no progress on literacy”. Now Brown can be expected to take this ‘success’ to a bigger scale.

Sir Michael Barber, formerly Head of TB’s Delivery Unit does know about education and since leaving the government has held positions first at McKinsey and then Pearson. Barber has worked extensively with DFID on education in Punjab, Pakistan – a task that he now describes as pro-bono work. However, it was not always so. In 2011 it was revealed that he was paid a daily fee of £4,400 for this work and that this was less than half his ‘normal’ rate. Like his ex-boss, it would seem that Sir Michael knows how to blend fees and pro-bono.

Finally, beyond specific individuals, the broader legacy of the Blair era is the increasing celebrification of aid with all its attendant glitz and self-congratulation. TB and Brown, basking in the company of celebs, brought Geldof and Bono into the aid policy world, anointing them as experts, and confirming that aid was a space fit for all the beautiful people to roam with credibility. Angelina Jolie, recognised (in terms of number of awards at least) as the “world’s leading humanitarian” is the current leader of the celeb charge. But now, with the news that David Beckham is launching the 7: David Beckham UNICEF Fund, a new rival celeb force may be set loose. Indeed, what with the sheer gushing intensity of celebrity attention, it’s hard to believe that we won’t have the whole poverty-suffering-injustice-bad-things-happening thing sorted out pretty soon. Tony Blair – what a legacy!